A Nutritionist's Guide to Expedition Eating

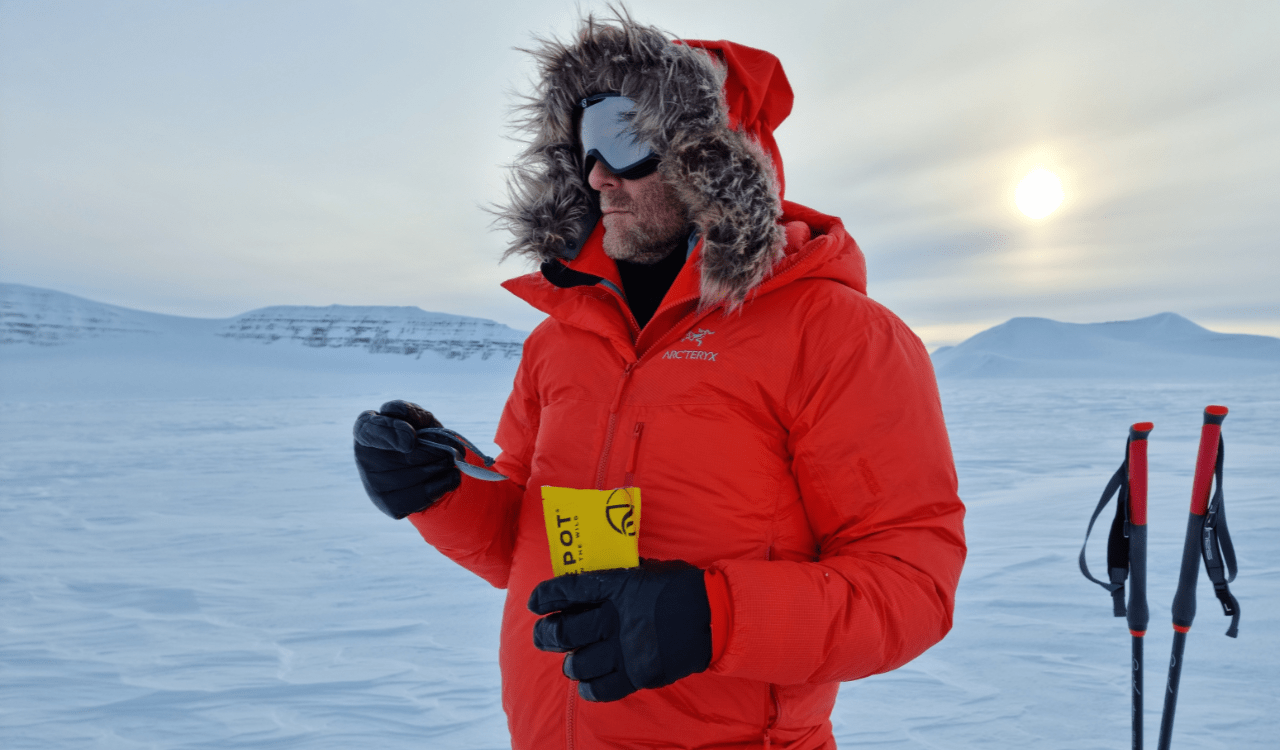

In 2023, Firepot worked with doctors Gareth Andrews and Richard Stephenson to curate a menu for an attempted unsupported ski crossing of Antarctica. The pair made it to the South Pole, but an unexpectedly short Antarctic summer season forced them to an early finish. Their expedition was made extremely challenging by severe storms, freezing temperatures of -30°C, and a near-impossible mission to make it off the continent before the end of the season.

Their nutrition, however, was perfectly calibrated, and the pair made it home safe and well. That was thanks to Gareth’s wife, Andrea Hordern Andrews, a Clinical Dietician from Sydney with over ten years’ experience. She’s also Director of Argon Expeditions, an antipodean company she co-founded with Gareth and Richard in the aftermath of their Antarctica trip. Together, they provide expedition planning and logistics consultation, as well as professional advice on medical and nutritional management. In this behind-the-scenes of a major expedition, we spoke to Andrea about what it takes to fuel a polar adventure and why the type of nutrition you choose can mean the difference between success and failure.

How did you end up working in expedition nutrition?

I started out as an Intensive Care Dietitian. I was drawn to that field because it’s the most challenging area of Clinical Dietetics: you work very closely with the medical team to provide adequate nutrition support for critically ill patients and prevent metabolic deterioration whilst they are acutely unwell. Over the next ten years parallel to my clinical role, my experience with expedition meal plans evolved. Part of that was because my husband, Gareth, began taking on polar adventures which pushed him to the limits of human endurance — in 2013, he skied to the Magnetic North Pole; in 2016, he made a full unsupported horizontal ski crossing of Greenland; in 2019, he made a full unsupported ski and pack rafting crossing of Iceland; in 2022, he took on an unsupported 350km closed ski loop in Svalbard. I also participated in several ultramarathons, developing a passion for self-supported multistage ultramarathon running with RacingThePlanet. If I wanted to compete, I needed to optimise my own nutrition too. I’ve adapted my clinical knowledge into achievable nutrition planning in remote environments, creating bespoke, light-weight meal plans for self-supported events, as well as forging a very good understanding of what products are available and where to source them.

What are the specific challenges involved in formulating nutrition plans for polar expeditions?

There are always unique elements to any expedition meal plan, whether taking place in a desert, mountain range, or on a polar plateau in Antarctica. The choice of foods will vary significantly depending on the climate and duration of an expedition. In polar regions, food needs to be non-perishable, safe to be stored for long periods of time in icy conditions. Supplies need to be thawed, prepared, and consumed with minimal preparation to lessen energy-waste and time exposed to the elements. For the 2023 Antarctica expedition, we transported over 100kg of food to the coast of Antarctica and packed it onto the sleds to be consumed over 75 days on the ice. Gareth and Richard travelled with a small camping stove to boil water and made hot meals by rehydrating them in the tent.

How does the need for lightweight food influence dietary choices when packing for a polar expedition?

It all comes down to the weight the explorers can carry; the longer the expedition the more supplies they will need. It depends on whether the expedition will be supported or unsupported. On a supported expedition, there may be food drops or caches along the way, so you can add in a few extra luxuries at each resupply stop. But for an unsupported journey, like Gareth and Richard’s, the individual will need to carry all their own food and fuel for the duration of the journey. For the Antarctica expedition, this added up to 75 days of food and fuel which weighed over 100kg for each member of the team. I accounted for approximately 6500-7000kcal per day, with 1.2-1.3kg of food per day per person, which equated to 90-100kg of food for the 75-day expedition. Our dietary choices were purely based on the highest ‘energy yielding’ nutrients i.e. food that provides the most calories per gram to meet the explorers macro and micronutrient requirements.

And how do you make sure that those lightweight foods don’t compromise on high-energy?

I did a lot of research on lightweight food sources of high caloric and nutritional value and devised a plan that consisted of having a high-calorie meal in the morning and evening when the explorers were in the tent. Firepot modified our dehydrated meals — 220 mains and 220 breakfasts — to make sure that Gareth and Richard were able to meet their target Recommended Dietary Intake. For the mains, that meant adding kale, broccoli, spring cabbage, cavolo nero and peanuts. For breakfast, Firepot made a special polar option, combining porridge oats, coconut milk powder, dried fruit, and granola. They then added peanuts, pumpkin seeds, goji berries, cashews, raisins and chia seeds.

Daytime rations tend to be trickier; these snack bags need to be accessed in the cold, wearing very large polar gloves and eaten quickly at rest stops. I recommended easy-to-access and nutritionally dense savoury snacks — cheese, beef jerky and pork sticks, as well as a sweet snack bag including eight different chocolate, protein bars, bounce balls and nut butters. I also prescribed a very high calorie, nutritionally complete drink for the first snack break and a recovery drink for when they finished skiing for the day.

What are the unique demands placed on our dietary system by prolonged physical and mental strain?

The sheer volume of food that must be consumed is extraordinary. The usual Daily Recommended Intake for an adult is roughly 2000-3000 calories. For the Antarctica expedition, I planned 6500-7000 calories per day. At the beginning, it seems like too much; the body has to adjust. But by the middle to end of an expedition the caloric deficit is much more noticeable. The daily caloric expenditure to ski 20-30km each day across Antarctica, while pulling a 160kg sled, maintaining adequate body temperature, and exercising full concentration to avoid hazards, ranges from 6000-10,000 calories per day. I recommend oversupplying to try to meet caloric expenditure because undersupplying creates a larger deficit. The knock-on effect is lessened physical performance including weakened immunity, poor skin integrity, muscle breakdown, poor concentration and general grumpiness.

Then there’s the question of hydration; in very dry conditions it’s important to keep liquid intake high. In Antarctica, Gareth and Richard needed to melt snow to source an average of 4 litres of water each per day. On a polar expedition, you also have to consider dental health; the prolonged exposure to an expedition diet — not to mention the necessity of chewing half-frozen chocolate bars and so on — can pose a big issue. The diet we eat also plays a crucial role in regulating bowel habits, so in Antarctica, I recommended a very high fibre breakfast with an addition of caffeine to try and regulate bowel movements before heading off onto the ice for the day.

When putting together an expedition dietary plan, how do you address the psychological aspects, like maintaining morale and avoiding food monotony?

Dietary choices should include as much variety as possible as well as different textures, striking flavours and a few luxury items to be enjoyed sporadically. I was fortunate that both Gareth and Richard have no dietary restrictions and are generally not fussy. One won’t eat white chocolate and the other prefers a mocha to a coffee, but in Antarctica, these quirks felt fairly manageable. I prepared a ten-day food roster so that meals wouldn’t become repetitive and focused on including real food that tasted good. To boost morale, I added a few extra luxuries too: every three days they’d have hot soup in the evenings, or sometimes a hot chocolate after dinner. To celebrate the end of each week, their Sunday ration packs had a chocolate pudding and some extra sweets. To celebrate milestones such as Christmas, New Year and Gareth’s birthday, I added a little Christmas pudding and a 60ml swig of Whiskey which they shared.

Is it possible to have a nutritionally adequate meal plan on a self-supported expedition if you have specific dietary restrictions or preferences, e.g. vegetarian, vegan, gluten-free?

The main difficulty with a specific dietary restriction is that you might be missing out on vital macro- or micronutrients. But it is absolutely possible, you just need to know where to source your food. Nowadays there is so much more variety available; several brands tailor their products to suit dietary restrictions and fortify them to be nutritionally complete.

Which single supplement gives the most value for its weight during an expedition?

Fat is essential for any expedition diet as the main caloric component. Historically, explorers used a lot of saturated fat sources such as butter, lard, or dried beef to increase the caloric content of their diet, but these days, that’s associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. I prefer a monounsaturated fat source and recommend neat olive oil, nut butters and avocado powder. In Antarctica, the most valuable food source was olive oil. Both Gareth and Richard took 60ml of neat olive oil with their breakfast and their dinner which provided 120ml per day or 966 calories. Neat olive oil can be quite unpleasant to drink and sometimes affect your gastrointestinal system, so prior to the expedition we gradually introduced olive oil into their diet, which they gradually became accustomed to.

Expedition nutrition doesn’t just begin once you’re on the road: you need to train with the right nutrition too for optimal performance. What kind of programme do you recommend for that?

Optimal performance is dependent on several aspects. For Antarctica, our strength and conditioning coach, Joe Bonington, formulated a rigorous programme including regular and intense physical training sessions. Gareth and Richard both gained around 7kg of lean muscle mass so that they’d have excess weight to lose when they were on the ice. They had to gradually consume larger volumes of food, as well as the olive oil. They both found it difficult during the run up to the expedition to incorporate the amount of food they needed into a normal day. Both of them are doctors so they spend long periods doing shift work on the go. We had to introduce high-protein, high-calorie shakes, and tailor their meal plan around specific days. My most important recommendation for optimum performance nutrition is to seek professional advice; it takes a while to modify and adapt your regular diet to meet such specific needs.

Why did you choose Firepot for the 2023 Antarctic expedition?

It was important to balance the need for compact and portable food with nutritional requirements. Due to the duration of the expedition, sealed and dehydrated foods were a necessity so that they didn’t perish or lose nutritional integrity. Losing your food rations would be an expedition-ending disaster. I did a lot of research on available foods and products. I chose to avoid heavily processed supplemental meals, and preferred to use real food that’s actually enjoyable to eat. Gareth and Richard have taken Firepot meals on all of their expeditions, and I now consistently recommend Firepot because once rehydrated, the meals taste and look like a home-cooked meal. You can tell they’re cooked by hand. The choice of ingredients and the nutritional composition of each meal suits an expedition meal plan superbly — as does the level of flexibility they offered in calibrating their existing menu to suit a specific need.

—

If you're interested in finding out more about expedition nourishment, click on the links to the articles below: