On Thin Ice

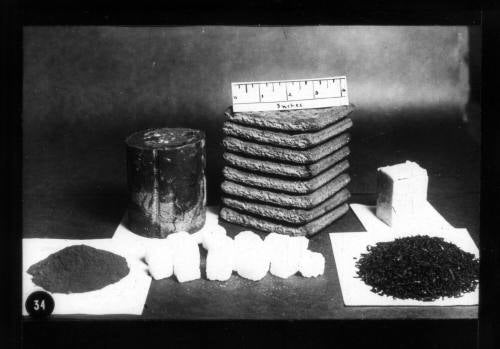

Pictured: 'One day's sledging rations' on Scott's Expedition in 1912, consisting of eight biscuits, butter, sugar cubes, tea, 'hoosh', cocoa, dried milk and sugar, and a tin of pemmican.

Antarctica has occupied explorers’ imaginations ever since Maori seafarers first — possibly — caught sight of it in the seventh century. But while there was a smattering of attempted exploration through the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries focused on mapping the coastline, it wasn’t until the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of exploration in the late nineteenth early twentieth centuries, that Antarctica’s mysteries truly started to be unveiled.

It wasn’t just the pack ice, fog and freezing weather that made the White Continent difficult to penetrate: the issue of food supply was a huge hindrance. Expeditions could last several years, with standard provisions including tinned tripe, hardtack (dry biscuits designed for a long shelf-life), pemmican (a mixture of dried and pounded meat combined with melted fat), and hoosh (a soup made of Antarctic ice, pemmican, and ground hardtack).

The psychological strain of an expedition was amplified by these unappetizing rations, a problem the Norwegian pioneer Carsten Borchgrevink tried to alleviate on his 1898 to 1900 Southern Cross Expedition — the first to overwinter on the Antarctic mainland. Borchgrevink assigned his crew a full schedule of research duties such as recording air and water temperatures, or fishing. Any new species were dutifully recorded, then cooked and eaten by individual crew members to see if they were safe. A later expedition found huge heaps of sledging gear, dead birds, seals and dogs abandoned on the ice by the party after they left Antarctica.

A few years later, when Robert Falcon Scott headed his doomed Terra Nova expedition from 1910 to 1913, even pony meat wasn’t enough to supplement pemmican in creating a healthy diet. Scientists estimate that his party was up to 3,000 calories short of the daily intake necessary to survive the physical rigors of Antarctic travel. The entire expedition perished from exhaustion, cold and hunger, just two months after reaching the South Pole.

Nutrition hadn’t changed much by the time Ernest Shackleton made his 1914 to 1917 Antarctic expedition, which has become the most famous of all polar journeys. But he faced an extra challenge: getting stranded for nearly two years after failing to cross the continent. After running through all their rations, Shackleton successfully led all 27 of his men to survive on a diet of sled dogs, penguins, seals, seaweed, and the odd morsel of elephant seal snout.

Today, things are a little different. Antarctic research stations — home to up to 100 researchers at a time — have professional chefs. Greenhouses grow fresh tomatoes. Tourists can eat caviar on cruise ships touring the Peninsula. But for the adventurer making any kind of unsupported traverse, the balance of calories, weight and nutrition is more than an art: it’s a science.

At Firepot, we’ve made polar expeditions something of a hallmark — a challenge which, when navigating the Antarctic either by dog sled or foot, can burn well over 6,000 calories each day. When Leo Houlding, Mark Sedon and Jean Burgun kite-skied across the continent to reach the remotest mountain on earth, we packed their meals specially to fit three portions into one, reducing their weight by 10kgs overall. More recently, we worked with expedition nutritionists for the European Space Agency (ESA), Stanford University and NASA to help Justin Packshaw and Jamie Facer Childs on their mission to travel 2,150 kilometres from the coast to coast of Antarctica, right through the frozen heart of the continent. Over the 80 day expedition, travelling by foot and kite, they relied on bespoke meals with extra vegetables, which helped improve critical nutrients in their polar diet. Earlier this year, we did the same for Dave Thomas, who at 68, became the oldest man to reach the South Pole on foot.

Date of publication: 22nd February 2024

Image credit: Australian National Maritime Museum.