The Psychology of Food in the Wilderness

To understand the powerful psychological impact food can have on expeditioners, Firepot talks to Dr. Nathan Smith — former research scientist at the MOD Science and Technology Laboratory, and founder of the online school for psychology, ‘In Extremis.’ His research into performance and health in extreme and challenging contexts — notably in space and polar environments — reveals how food can be used to overcome the psychological strain of exploration.

Motivation

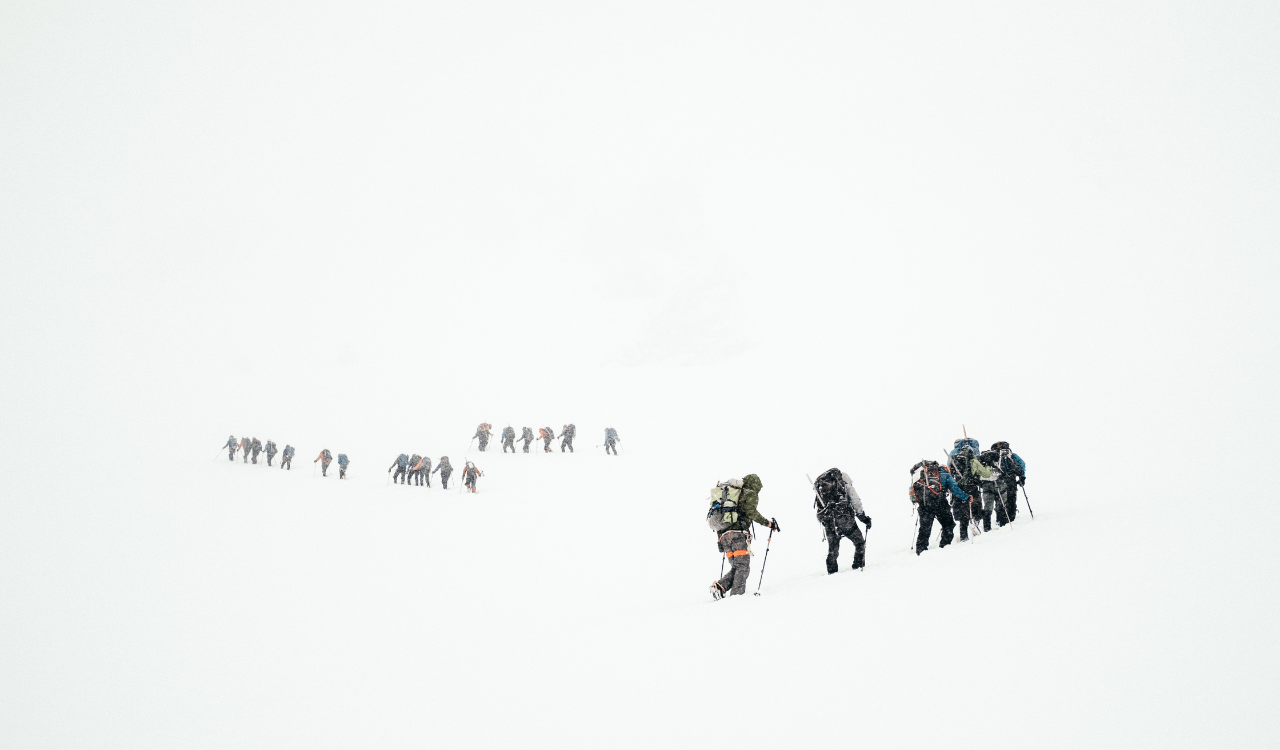

On any expedition, whether it be a weekend hike or an Arctic exploration, there are three main stressors to be aware of: the physical strain of external factors, such as extreme weather conditions, exposure and altitude; the psychological pressures of fatigue and monotony; and the social stresses that can arise from tensions within a group. Being able to adapt to these demands increases the likelihood that people will be able to stay psychologically well and make effective decisions. Good nutrition is a basic physical requirement, but food can also be used as a powerful psychological tool — one that can influence the outcome of an expedition and determine the safety and survival of those involved.

Motivation for running a race, embarking on an expedition or taking on a new challenge can vary enormously between individuals. In group settings in particular, variation in motivation can cause conflict. However, studies show that food plays a significant role in managing — and even alleviating — stress while out in the wild. Not only does it raise morale, it has been shown to provide the motivation individuals need to persist in extreme settings.

As the explorer Ben Saunders will testify, even when you have company, just the thought of food can take up several hours of the day. The journal he kept during his 1,000km ski expedition across Antarctica, reveals that ‘food became the repeat topic all week, with ‘food fantasy of the day’ quickly becoming the substitute for song of the day.’ However, in the end, Ben and his expedition partner, Tarka L’Herpiniere, were so hungry that they had to stop sharing their food fantasy daydreams. The diary also shows how differently people use food to boost their morale: Ben would devour his chocolate bar halfway through the day to break up the monotony of eating energy bars, whereas Tarka would save his until the evening and break it up square by square.

This underlines the importance of rewarding yourself with food after reaching a milestone in order to provide the motivation you need to get over the finish line. This was something Sir Edward Hillary appreciated in the early days of the exploration of Everest. He allowed each member of his team to add their favourite food into a ‘luxury box’, so they each had something to look forward to opening as they neared the top of Everest on their quest in 1953.

Variety

In low stimulation settings — such as the unchanging view of ice sheets, where it is hard to measure progress, or endless ocean waters — a person’s motivation can easily become suppressed. If food is too bland and repetitive, this stress can be compounded further. This in turn leads to dwindling appetites and further lack of motivation.

Mealtimes have the potential to break the monotony of the day by introducing new sensory experiences with varied textures and tastes. Perhaps this is why John Young, the commander of the first ever space shuttle mission, famously smuggled a corned-beef sandwich in his spacesuit pocket for the journey in 1965. NASA, now recognises the importance of variety, and offers astronauts 200 food and beverage options to choose from.

Back on Earth, we repeatedly receive feedback on how important variety is on the expeditions we support. Sometimes this comes in unexpected forms, as Lukas Haitzmann discovered during his record-breaking row across the Atlantic when a flying fish landed in his boat. “I tried drying it out in the sun, and then eating it” he says “but I definitely don’t recommend”...

Cohesion and team work

A reminder of home

During extended expeditions, creating any sense of normality can have a powerful effect by alleviating homesickness. This is why some of our expeditioners have been known to bring psychological support kits from friends and family. Mathieu Tourdeur — the youngest and first Frenchman to reach the South Pole — recounted how he benefited from listening to audio recordings from his friends: “I burst out laughing into my mask in the wind. It was absurd… But I was mostly surprised how good it was to laugh. The sky became less grey, the sledge lighter and the loneliness more bearable.”

During extended expeditions, creating any sense of normality can have a powerful effect by alleviating homesickness. This is why some of our expeditioners have been known to bring psychological support kits from friends and family. Mathieu Tourdeur — the youngest and first Frenchman to reach the South Pole — recounted how he benefited from listening to audio recordings from his friends: “I burst out laughing into my mask in the wind. It was absurd… But I was mostly surprised how good it was to laugh. The sky became less grey, the sledge lighter and the loneliness more bearable.”

In the same way, meals or snacks can have the same effect, and it is not unheard of for explorers to make space for the odd home-cooked meal in their bags. In 2017, explorer Leo Houlding and his teammates did just that when trying to reach one of the world’s most remote peaks, The Spectre, by packing frozen pre-cooked meals for 'treat' days, including trays of home-made cheesecake.

DREAM FOODS:

Kiko Matthews, 49 days at sea rowing the Atlantic

“Anything fresh! Mojitos, vegetables and cold liquids. I dreamt about broad beans, fresh broad beans where I was popping and eating them out of the pod.”

Adam Kimble, 25 hours of running Beyond The Ultimate’s Desert Ultra in Namibia

"It usually takes about one or two stages before I’m craving just about everything! For me, it’s normally the same indulgences that I allow myself to have post-race: pizza, ice cream, beer, and soda spring to mind!"

Leo Houlding, 65 days in the Transantarctic

“Three bottles of Champagne and huge slab of fresh meat”

Mark Beaumont, 80 days circumnavigating the world by bike

“My mother’s homemade cheesecake — I’d have eaten it all in one go. And then I’d have asked for a fillet of monkfish, wrapped in pancetta with vegetables.”